Meet Anna Robinson, a British volunteer who volunteered as a VSO teacher trainer in Nepal in 1985. 30 years on from first arriving on her placement, Anna has returned to Nepal. In this blog Anna shares her highlights and learnings from her experience.

Why did you decide to volunteer with VSO?

"It was 1985 when I applied for VSO, so some time ago. I had intended to do it when I was at university. You had to have a vocational qualification and professional experience before you could volunteer with VSO.

After completing an English degree, I decided to train as a primary school teacher and worked in London. I knew that I wanted to volunteer with VSO afterwards, so I thought that would be an interesting course to take.

I was very aware of VSO during my undergraduate days. After completing my Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) in London, I applied to VSO and got a position as a Primary Teacher Trainer in Nepal.

From those beginnings, I continued working in the development sector, including three years as a VSO field officer in Nepal and working with ActionAid London covering Nepal and Bangladesh. After that, I transitioned into academia and have been a Professor of Education for the last 20 years.

What was it like when you first arrived in Nepal?

I suppose it was unusual because I was working on an educational project, called the Seti Project, that covered three districts. I wasn’t based in one school or location. I was job-sharing with another VSO teacher, Kathy, and our roles meant we were constantly travelling.

We were working in the far west of Nepal, which at that time was an extremely remote area with no roads at all. We had to fly from Kathmandu, which took about an hour and a half. Travelling between districts required three days of walking!

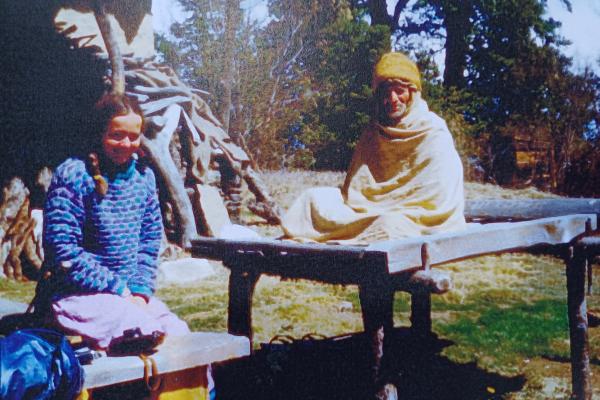

We worked with a team of Nepali teacher trainers, going from village to village, staying in schools, working with teachers, and then moving on to the next district. It was a unique opportunity. I once calculated that I worked for 10 days a month and spent 20 days walking. And when I say walking, it wasn’t on flat terrain—it was up and down mountains.

The biggest challenge for me was physical. That area of Nepal was a food-shortage zone at the time. The government and aid agencies had to bring in rice because not enough food was grown locally.

VSO Kathmandu started sending us food parcels because getting sufficient protein was nearly impossible.

In terms of how communities reacted, it was an incredibly positive experience. There were no other development projects in the region at the time. The far west of Nepal was neglected, and our project—funded by the Nepal government, UNDP and UNESCO—was focused on developing an educational curriculum tailored to the remote area and establishing teacher training facilities for the first time.

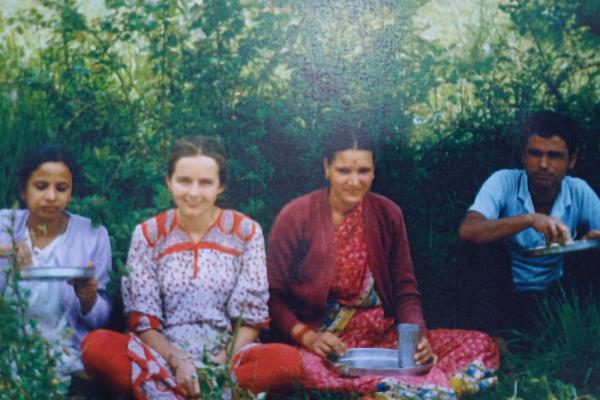

Because I was a woman, I was asked to work on the Cheli Beti programme, which means ‘young girl’ in Nepali. The Seti project ran early morning literacy classes for young girls who didn’t attend school. These classes were held from 7:00 to 9:00, before the girls started their household chores.

My work involved collaborating with a local young woman to run these classes, writing literacy materials in Nepali, and training young girls—many of whom had only completed primary school themselves—to become teachers for younger girls. This became my primary role for much of the time.

At that time, there was no other development activity in the area, which made the work feel especially significant.

When did you and your team know that you were making a difference?

I wouldn’t distinguish my own impact from the rest of the team because it was very much a collective effort. What stands out to me, especially in retrospect, was the work we did with women.

For the Cheli Beti programme I mentioned, we ran a three-week residential teacher training programme exclusively for girls. We recruited girls from across the district, bringing them to a high school where they lived with us during the training. The programme focused on basic literacy, teaching skills, and practical development activities like constructing a latrine. For many of these girls, aged 15 to 16, it was their first time leaving their village.

It was a big deal. Their fathers only agreed to let them come because they knew they’d later be paid as teachers, which was an economic incentive. But during those three weeks, the experience was transformative. Meeting other girls from different districts, they encountered a sense of empowerment and community.

We consciously eliminated taboos during the training, such as caste-based discrimination and restrictions around menstruation—like barring girls from classrooms or communal meals during their period. It created a microcosm of a different, more inclusive society.

The training itself was incredibly positive, and the girls gained so much from those three weeks. However, when they returned to their villages, they were on their own. They’d glimpsed a different way of life, had their aspirations broadened, but found themselves back in their traditional domestic roles, often married off young.

Interestingly, about three years ago, I revisited the same area and reconnected with some of the Cheli Beti teachers. That experience was incredible because some of them had become political leaders or taken significant steps to change their lives.

Some had decided not to get married. It was clear that the programme had a huge impact—not just through the training itself but also by providing them with income and teaching skills. That, I think, was the most significant impact of the project.

What compelled you to come back to Nepal after 30 years?

I’ve returned to Nepal every year because my husband is Nepali, so I have family here. My professional work has also kept me connected, as I have established university partnerships with institutions like Kathmandu University and Tribhuvan University.

I’ve been collaborating with the same research centre I worked with during my time as a VSO volunteer, Tribhuvan University centre for educational research, CERID —it’s still going strong after 40 years. So, it wasn’t a sudden decision to come back to Nepal.

I’d been working in Kathmandu and other districts, but I hadn’t revisited the far west, where I had volunteered, until recently. It was mostly curiosity that drove me back there, wanting to see what had changed. I’ve witnessed massive changes in women’s lives in different parts of Nepal where I’ve lived.

My PhD research focused on a western area called Arughat, not as remote as the far west. I lived there for a year with my young son, working with women in literacy classes to explore how education and development were impacting their lives.

That has remained my academic interest: understanding how change comes about in people’s lives and the extent to which it’s linked to literacy, education, or other factors.

The private sector and communication advancements, such as mobile phones, have had a profound impact. For instance, in the far west, I met women who had become political leaders, partly because of greater access to communication tools. Parents even shared concerns about girls arranging their own marriages through Facebook, highlighting how traditional practices are shifting.

Reflecting on your experience, what do you think contributes to the long-lasting impact of VSO programmes?

The projects I’ve discussed so far touch on broader themes of development, but I think it’s important to focus on VSO’s unique approach and the role of volunteers.

VSO operates differently compared to other development models, and from my perspective, my time as a VSO volunteer was both the most challenging and the most creative period of my life. I had the freedom to design my own role, which is something I think sets VSO apart.

Unlike roles with rigid job descriptions, volunteering with VSO often allows for more flexibility and opportunities to build relationships and initiate new projects that might not fit within more bureaucratic systems.

One key challenge is embedding innovative practices within the organisations we work with, ensuring that the projects don’t just fade away when the volunteers leave.

From my experience, the most enduring impact of VSO isn’t just on the communities but also on the individuals involved—particularly the teams of teacher trainers, staff, and volunteers themselves.

For instance, the team I worked with remains a source of inspiration, and we’re currently planning a book about our project and its implications for education in Nepal today. It’s remarkable that even as many of us near retirement, the bonds we formed and the lessons we learned remain powerful.

Looking back, the experience was life-changing—not just for me, but for everyone on the team. Living and working together in a remote area taught us a great deal about ourselves and about education under challenging circumstances. I think this personal and professional growth is one of the most significant impacts of VSO’s approach.

How did this volunteering experience impact you personally and professionally?

It completely transformed my understanding of development. Like many volunteers at the time, I went in with the mindset that I was there to "help" what was then referred to as the "Third World." I came out of it realising that I had gained far more than those I thought I was helping. This shift in perspective altered my entire approach to development work.

The experience also gave me enormous confidence. It was exciting to work independently while being part of a supportive team. I learned how to develop initiatives and create curricula that genuinely reflected the needs of the communities I was working with. This was incredibly rewarding, even though it was a challenging experience.

Professionally, the skills and insights I gained shaped my later career. After VSO, I worked with ActionAid in London, focusing on development education, which was deeply influenced by my VSO experiences. That foundation in human-centred development informed my transition to academia, where I continued exploring the dynamics of education and development.

What I learned most from my time with VSO is that successful development is fundamentally about human relationships. Those connections—with communities, colleagues, and partners—are the true catalysts for sustainable change. Over time, as development trends have become more focused on structured programmes and technologies, I’ve noticed the human element sometimes gets side-lined. For me, the relationships formed through VSO were invaluable.

Did you maintain these connections and relationships?

Yes, the relationships I built during those years became lifelong friendships. We had shared such intense experiences, living and working together in a remote area for two years. That kind of bond is hard to break, and I still meet up with many of my colleagues in Kathmandu.

The hardest relationships to maintain, though, were with local staff—particularly the women. A couple of years ago, I reconnected with the young woman who had worked with me on the Cheli Beti programme.

Meeting her again was incredibly emotional; we both burst into tears. However, it was bittersweet, hearing about the difficulties she continued to face working in such a remote area. This reinforced how uneven progress can be.

What advice would you offer to someone considering joining VSO as a volunteer?

One of the most important considerations is the kind of role you’ll take on and the sustainability of your impact. For me, it was crucial to work as part of a team where I could have a lasting effect, rather than simply filling a gap in the system. Ideally, the role should involve collaboration—whether you’re training someone or learning from them—rather than just replacing a local worker for a set period.

I’d also advise going in with an open mind. Volunteers who struggled the most were often those with rigid ideas of how their skills should apply, based on their experiences back home. They found it hard to adapt to local contexts and realities. In contrast, those who approached the role with curiosity and humility often had the most rewarding experiences.

Interestingly, VSO’s focus on recruiting experienced professionals sometimes created challenges. Many volunteers came in confident about their expertise in fields like nursing or forestry, only to realise they needed to adapt significantly to the new environment. Recognising that you may need to relearn your skills in a completely different context is essential.

What are your aspirations for the next 10 to 15 years?

Having recently retired as a professor, I’m at a crossroads. My most recent research, completed with the University of Sussex, focused on public health in Nepal and the Philippines. Looking ahead, I’m interested in exploring how education can better support women whose lives have transformed in unexpected ways—many of whom are highly mobile and have worked in places like Kuwait as domestic workers.

Education in Nepal still follows a very traditional path, while women’s lives are evolving in ways they could never have imagined. My goal is to explore how education can better align with these changes and help women take charge of their futures.

This might involve working with groups of women to develop new interventions that address their specific needs and aspirations. It’s an exciting challenge, and I’m looking forward to seeing where this next chapter takes me."

Learn more how you get stay connected with our global network of volunteers

Read more

In photos: Our Regional Health Promotion Conference 2025

Check out some of our favourite photos from Regional Health Promotion Conference (RHPC25). This event sought to reimagine Universal Health Coverage through the lens of intersectionality.

Using intersectionality to create healthy beginnings and hopeful futures

World Health Day brings global attention to the urgent need to end preventable maternal and newborn deaths. Learn more about how our Regional Health Promotion Conference is tackling these issues head on.

Highlights from the Regional Health Promotion Conference 2025

The Regional Health Promotion Conference 2025 reimagined Universal Health Coverage (UHC) through the lens of intersectionality, by bringing together experts from across East Africa and beyond.