For girls living in extreme poverty in Kenya, the “bride price” on their heads is a ticking time bomb. With millions of girls forced out of school to marry, a VSO project is proving it’s never too late for them to catch up and reclaim a better future.

When educating girls becomes too expensive for poor families, marriage can be the only viable option, often before they reach secondary school. Girls taken out of school for marriage rarely go back to finish their education, and many are pregnant soon after – further limiting their freedom and independence. Not only that, but to “prepare” for marriage, many of them endure painful and traumatic female genital mutilation (FGM). Despite the practice being banned in 2011, a 2020 report by Unicef states that four million Kenyan girls and women today have undergone FGM.

Projects, programmes and government-funded education have made huge progress in supporting girls’ education over the last decade. But now in 2020, the coronavirus pandemic threatens to undo these victories, pushing girls’ rights to education and independence back ten years – perhaps more.

An education for life

VSO’s Education for Life project supports girls that were denied their education, running catch-up centres where they can learn the vital skills they need to be independent and successful in their own right.

Girls can attend the centres free of charge and learn maths, English, and Swahili with qualified teachers. They're also matched with a woman from their community as their mentor, who offers life skills, support and advice.

The coronavirus pandemic meant the centres had to close along with the schools. During lockdown, they made sure the girls had supplies to keep up their studies at home, as well as hygiene kits and regular wellbeing check-ins.

Thankfully, the centres were able to open safely before the schools did, but during lockdown, many more girls have been forced into early marriages and will never go back to school. For them, catch-up centres like these could be their only chance to have the future they hoped for.

“I was asking myself why I had to leave school.”

Just like her mother and grandmother before her, extreme poverty meant Consolata couldn’t finish her education.

“I left school and got married early because my family didn’t have much money – I was 14 years old.”

Although Kenya has free education, even this can be out of reach for some, with the cost of books and uniforms. Consolata’s parents couldn’t afford to send her to school as well as her brothers, so she watched from the side lines as her peers drew ahead of her.

“I was asking myself why I had to leave school while others continued, especially because I know that schooling helps you get a good life.”

I feel good now because I am remembering what I had forgotten.ConsolataStudent, Education for Life project

Seeing his daughter’s distress, Consolata’s father suggested she take a hairdressing course. But while she was away, her father got sick and, when she returned home, he died

After her father’s death, there was no more money for school and Consolata got married – but tragedy would soon strike again.

“I had a happy life with my husband but unfortunately, he also died – I was pregnant at the time. I got sick and was taken to hospital where they operated on me. My mum was with me and I recovered, and we went back to her home with the baby. That is where we live today.”

Since returning home, Consolata has been attending a VSO catch-up centre. Her mother encourages her to go, looking after the baby while Consolata focuses on her future.

“I joined the catch-up centre because I know it will help with my future. I like my teacher Christine; she teaches me so well that I am learning what I’d forgotten. I had forgotten multiplication, subtraction and addition but now I can do them all – maths is my favourite class.”

Consolata still has her sights set on becoming a hairdresser, and is hoping that finally having the chance to finish her education will set her on the path to success.

“I know education will help me have a brighter future.”

“I didn’t want the children in my community to face the same problems I did.”

Christine dreamed of becoming a teacher since she was in primary school. She had been inspired by one of her own teachers, captivated by the way she led her own life and inspired by the way she taught.

When Christine’s family couldn’t afford to send her to school and pressured her instead to stay at home to help with the children and housework, she held on to that ambition to teach. She payed her own school fees by working on people’s farms and finally achieved her dream. Now, she wants to use her experience to help others.

Christine now teaches in the same catch-up centre that Consolata goes to.

“I didn’t want the children in my community to face the same problems as I did. It was a big struggle for me, but I did make it in the end.

“Some girls have such difficult lives because of poverty – they see their parents struggling and they work in people’s shambas [small farms] for money – so in the end they want to get married so they can fend for themselves rather than their families.”

Teaching these girls has some challenges, but it means I’m learning too. It has really opened my mind and shown me how to deal with different challenges and people.ChristineTeacher, Education for Life project

She uses her own struggles to help understand the challenges they’re facing and has found that the girls inspire her as much as she inspires them.

“The girls in my class tell me that they want to become hairdressers, they want to open their own business. They have ideas for their futures now. For example, some of the girls didn’t know how to add or subtract, now they will be able to give change to their customers.

“My favourite part is seeing the girls progress and change, seeing how they were when they first arrived and how they are now – it means I’ve done something as their teacher.”

“If you educate a girl, you educate the whole world.”

Growing up, Janefer’s parents were supportive of her education and encouraged her to stay in school – even though, or perhaps because, they weren’t able to complete their own educations.

Experiencing the benefits of an education first hand means Janefer knows how transformative it could be for, not only young girls, but the families and communities that surround them.

“Getting an education is important, it means we can have a good life, it enables us to teach our children. If you educate a girl, you educate the whole world. We tell the girls at the catch-up centre that, if they get an education, they will be able to support their children and bring up their family to look like a family.”

As a mentor at an Education for Life centre, Janefer supports the girls at with their struggles inside and outside of academia – from problems at home to mental health to practical life skills. Though most of the girls are married and many have children, they are still children themselves, and need the same love, support and guidance as any teenager would.

When they understood what it could bring them, parents started thinking ‘we will go and pay school fees and buy books for our daughters.JaneferMentor, Education for Life project

“I mentor six girls at the centre. I can guide them with what they should do next after completing their studies and show them they have different options,” she says, “I tell them their life will change from where they were – that their lives will be as good as they expected.”

Many of the girls have had traumatic experiences, and part of Janefer’s role is to support their mental and emotional wellbeing, helping them to heal and move forwards with their lives, using the structure of the classroom for stability.

“I talk to them about self-esteem – what it is and how it will help them focus and calm their minds. I tell them to relax and go step-by-step with the curriculum. They don’t have to fear anything.”

As well as seeing the transformation in her young mentees, Janefer says she’s seen a change in the community since the centre opened. She says that the project is opening people’s eyes to girls’ worth, not just as wives and mothers but as individuals. They see that letting girls thrive benefits society as a whole, and how education is the key to unlock this potential.

“I have seen things change in this community since VSO started working here. Before, people saw education as a useless thing,” she says.

“Now so many girls want to come because they have seen the impact of the project. People are expecting that they will get something good into their lives. That is why they are allowing their daughters or wives to come and learn at the centre, so that at the end they will also receive the light.”

And as the word spreads, the benefits ripple outwards, even touching the lives of other girls who may have otherwise faced the same fate of early marriage and unfulfilled potential.

“If the girls go on to open small businesses, business will flourish and it will expand us. This centre will grow because our community has started improving. There are many more girls who need the catch-up centre, who are hidden somewhere, who don’t come out. If you open another centre, more girls who are struggling can come and they can be helped too.”

The Education for Life project is active in five of the most marginalised counties in Kenya, and aims to reach 5,000 girls aged between 10 – 19 years old who are not in education.

Read more

'Here's to every volunteer' - an inspiring song from volunteer and artist Larry Dwayne

Known in the music industry as Larry Dwayne, Lawrence Ochieng is a Kenyan volunteer, hip-hop artist, and activist who uses his platform to raise awareness about climate change. Listen to his original song, 'Volunteer'.

Meet the 2024 Volunteer Impact Award winners

Our annual Volunteer Impact Awards celebrates the incredible impact made by VSO volunteers across the world. Learn more about our four 2024 winners.

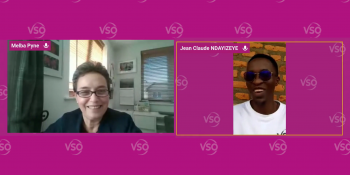

Video blog: In conversation with two education volunteers in Rwanda

Melba from Colombia and Claude from Rwanda are two very different education specialists with one thing in common, they both volunteered with VSO in Rwanda. We brought these two volunteers together to share their reflections on what it was like to volunteer with VSO. Watch the videos now.