In Nigeria last year, six times more people were killed in clashes between herdsmen and farmers than in attacks by terrorist group Boko Haram. So why aren’t we hearing more on this issue?

“Fulani herdsmen brought their cattle to graze on my farm, on my lush green maize. They brought out their machetes and threatened to kill me.”

In Wushishi, central Nigeria, Abdullahi Markusidi is still reeling from an encounter with a group of nomadic Fulani herdsmen a few months ago, who were seeking land to graze their cattle on.

“It’s dry season but I irrigate my farm so my crops can grow, which attracted the herdsmen. They carry machetes and you never know whether it will be used to harm you if the herdsman feels under threat.”

“I find it hard to trust Fulani herdsmen because they appear friendly, they will even smile and make conversation with you but when your back is turned the same person can raid your farm.”

Abdullahi, whose farm has been supported through VSO’s Improving Market Access for the Poor (IMA4P) project through workshops on farming techniques and financial management, says farmers here have been locked in an under-reported battle with Fulani herdsmen for the past 20 years.

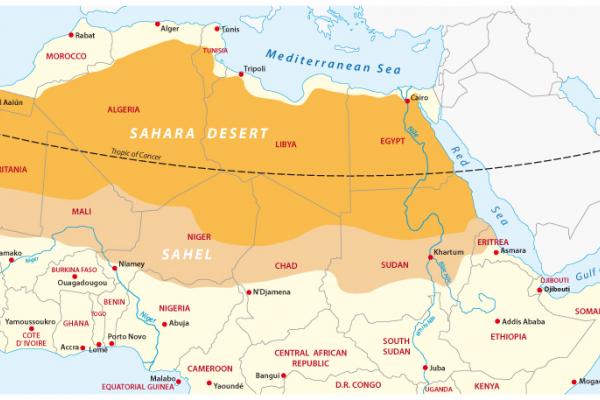

The Fulani once occupied the Sahel, an area of land just below the Sahara desert.

However, climate change is turning this semi-arid land into desert, prompting migration south into Nigeria, Niger, Senegal, Ghana and Mali.

This, as well as increased demand for land in Nigeria, has ramped up tensions between farmers and herdsmen.

The number of clashes between the two sides has mushroomed, from 67 between 2007 and 2011, to 716 clashes between 2012 and 2018.

Although thousands of people have been killed and displaced through this conflict, the conflict rarely makes headlines outside of Nigeria, making it one of the world’s most underreported wars.

Clash of cultures

The conflict is far from straightforward, with frustrations on both sides: farmers see their crops destroyed by livestock, while Fulani herdsmen see their way of life under threat as grazing land is repurposed for agriculture.

“It's a very difficult subject to touch upon, because you are talking about somebody's culture, somebody's way of life,” says Mariam Shehu, coordinator of VSO’s IMA4P project in Nigeria. The project is skilling up communities in modern farming techniques and giving farmers methods of adding value to their crops.

“Fulanis are nomadic. They are used to free movement,” said Mariam.

Following the tensions on his farm, Abdullahi and neighbouring farmers met with a local advocacy group promoting the welfare of Fulani herdsmen in Nigeria.

The group asked herdsmen to refrain from grazing their cattle on people’s farms, but this isn’t necessarily effective.

“Since the attack they have not returned but have attacked other farmers,” said Abdullahi.

Negotiations with the herdsmen led to Abdullahi being paid 50% of his losses, but he says this does not cover the resources he has invested on the land.

“It hurts my pride to even take the money but it’s better than nothing,” said Abdullahi, who has also seen some of his harvest hit by flooding this season.

VSO’s work in Niger state is encouraging conversation and strengthened leadership in communities.

Abdullahi said, “Skills learnt under the IMA4P project, like meeting people from both sides to discuss challenges, and negotiating our wants and needs, has come in useful in addressing conflicts with the herdsmen.”

Meeting in the middle

Yusuf Abdulrahman, 62, was born into a family of herders and farmers and is now a volunteer with VSO’s IMA4P project.

“My ancestors are Fulani, so we keep cows and animals. I grew up on a farm owned by my father.

“The IMA4P project is helping. Herdsmen don't have to depend on their cows only, they can farm too. With the herdsmen farming, this reduces the clashes.

“That’s because if I allow my cows to eat up your farm, tomorrow they will eat up my own. The farmers are also encouraged to keep livestock, so farmers know how to protect their farm from livestock.”

Farming co-operative groups, which give farmers the chance to pool their crops to get a higher price at market, have been strengthened through the IMA4P project, by training members in leadership skills.

“In the co-operative groups, there is no distinction (between farmers and herdsmen). The farmers and the herdsmen can be in the same cooperative group.

“Since they are in the same group, they protect the interests of one another. The IMA4P project has encouraged integration between these two communities.”

Keeping the peace

The Nigerian government has been criticised for not doing enough, with many calling for the clashes to be addressed through changes to policy and legislation.

Abdullahi, who is now trying to recoup lost earnings, says: “I think that if herdsmen are educated on the consequences of their actions they may change their mindset.”

VSO has been partnering with local organisations, like the All Farmers Association of Nigeria (AFAN), to achieve peace between the two sides.

Shehu Galadima, the director of AFAN, said, “We want to make sure that there's peace and harmony within these communities.

“A herdsmen can be a farmer, a farmer can be a herdsmen. We need to improve the relationship because we are the same family.

“So we try to make sure that we are also moving together. Everything should be done together, as a community, to resolve the issue.”

Read more

Nowrin vs female farmer poverty

As the sole female volunteer on VSO’s rural livelihoods programme in Bangladesh, Nowrin Sultana, 26, is in demand. For the last two years, she’s been working to financially empower all-female farming groups in rural communities in the northern district of Rangpur.